Trump's travel ban fuels anxiety in South Africa, even though it's not on the list

Johannesburg — On most mornings, dozens of people line up and wait for appointments outside the U.S. Consulate in Johannesburg, South Africa, many seeking applications for visas to travel to the U.S. It can take up to five or six months just to get one of the appointments.

On Thursday, a chilly winter morning in South Africa, CBS News found hopeful travelers in the line worried about what could happen if they do make it to an arrival gate at a U.S. airport, or during their visits.

President Trump's announcement on Wednesday of a looming travel ban on all citizens from 12 nations in Africa and the Middle East didn't even include South Africa, despite the American leader's tetchy relations with the country. But the anxiety caused by the return of blanket travel restrictions — something Mr. Trump did during his first term, too — was almost palpable in Johannesburg.

One person in the line said they were planning to travel for a work conference, but they wondered whether it was a good idea.

Another, tentatively planning to travel for non-essential reasons, worried that, with the last name Assad, it might be better to skip the planned trip entirely.

"Do I run the risk of being rounded up and sent to another country, or even jail?" they asked. "The risk is simply too high."

No one in the line would give CBS News their full name — out of fear, most said, of any public comment possibly bringing a denial of their visa request.

What African countries are facing Trump's travel ban, and why?

Nationals of seven African countries are facing a ban on travel to the U.S. from June 9, per Mr. Trump's announcement: Chad, Somalia, Sudan, Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea and Libya.

Three of those countries — Sudan, Somalia and Libya — were among the countries put under a travel ban during Mr. Trump's first term in January 2017, though the restrictions on Sudan were later dropped, and those against Somalia and Libya were eased.

Many of the 12 countries on the new list have been wracked by repressive regimes and plagued by conflict.

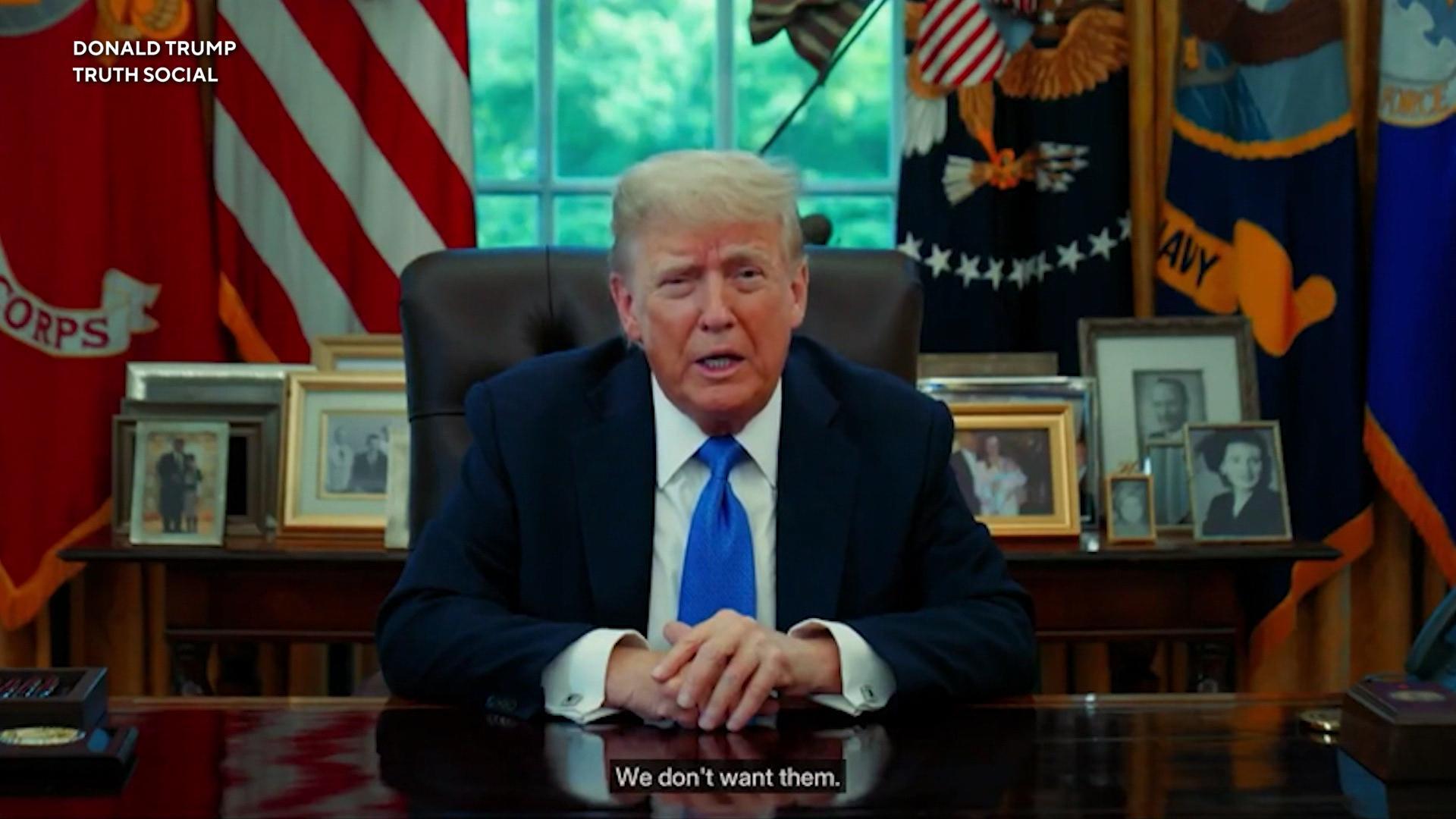

"We don't want them," President as he announced the ban on Wednesday, which he said was needed "to protect Americans from dangerous actors."

He cited risks ranging from terrorism to people overstaying their visas, and stressed that the U.S. "cannot have open migration from any country where we cannot safely and reliably vet and screen those who seek to enter."

Somalia was cited by the president as being a "terrorist safe haven," while Libya, he said, had a "historical terrorist presence."

"The recent terror attack in Boulder, Colorado, has underscored the extreme dangers posed to our country by the entry of foreign nationals who are not properly vetted, as well as those who come here as temporary visitors and overstay their visas," Mr. Trump said.

Critics noted that the man charged in that attack, Mohamed Sabry Soliman, is an Egyptian national, and Egypt is not included on the travel ban list announced by Mr. Trump on Wednesday.

Somalia immediately responded to the American leader's proclamation, with the country's Ambassador to the U.S., Dahir Hassan Abdi, saying in a statement that, "Somalia values its longstanding relationship with the United States and stands ready to engage in dialogue to address the concerns raised."

Mr. Trump said in his remarks that "the United States must be vigilant during the visa-issuance process."

The Africa Union issued Thursday asking the U.S. to adopt a more "consultative approach" with the countries named by Mr. Trump, adding that it was concerned about the "potential negative impact on people-to-people ties, educational exchange, commercial engagement, and the broader diplomatic relations that have been carefully nurtured over decades."

It has long been difficult and laborious for people from many African nations to get a visa to travel to the U.S.

Mr. Trump's announcement came, however, just days after a second group of South African Afrikaner "refugees" left on commercial flights bound for the U.S. under a program announced by the White House in February, which fast-tracks resettlement of the white South Africans even as the administration works to suspend other refugee programs.

President Trump has repeated false claims that a white genocide taking place in South Africa, claiming Afrikaner farmers are the victims of systemic, racially motivated violence.

In January, South Africa adopted a land expropriation bill that allows the state to take ownership of land to address racial disparities in ownership. To date, no land has been expropriated without compensation in South Africa, despite claims by right-wing activists in the country — and some prominent supporters outside South Africa, including Elon Musk — to the contrary.

Soon after the bill was passed, in a briefing with journalists, Mr. Trump accused the government of South Africa of "doing some terrible, horrible things," and he said in a social media post that he would be, "cutting off all future funding to South Africa until a full investigation of this situation has been completed!"

As relations between the two countries deteriorated, President Cyril Ramaphosa traveled to Washington late last month with a raft of new measures to try to mend ties. But President Trump ambushed him in the Oval Office, with news cameras rolling, with a video he claimed as proof of the so-called white genocide.

The video included clips of controversial South African opposition figure Julius Malema singing a song that became popular during the anti-apartheid struggle, called "Kill the Boer," which means Afrikaner.

Ramaphosa watched the video and then pointed out to Mr. Trump that the views voiced in it were not government policy, before conceding that South Africa undeniably has a violent crime problem — but that only a small number of white farmers had been targeted.

Ramaphosa's two hour meeting with President Trump was largely seen as productive from the South African point of view. Ramaphosa had hoped to leave the White House with an assurance from Mr. Trump that he would attend the G20 summit in South Africa in November. He didn't get that, but the U.S. leader said he was considering it.

The U.S. Embassy in South Africa later issued a , saying that to qualify for U.S. resettlement, applicants "must be of Afrikaner ethnicity or a member of a racial minority in South Africa and must be able to articulate a past experience of persecution or fear of persecution."

Across Africa, there was already a sense of confusion and sadness over the relentless aid and trade cuts brought by the Trump administration, and the travel bans have only exacerbated that feeling.

"Maybe Americans just don't like us anymore," suggested one woman in the line outside the U.S. Consulate on Thursday.